Malnutrition threatens to derail Tanzania’s education development

What you need to know:

- Data shows 31 districts in regions where nearly a third of children have been affected by malnutrition, their performances in the 2016 primary school leaving examinations (PSLE) were poor.

- Chronic malnutrition affects the growth of children below the age of five, impairing their brains.

Mbeya. Malnutrition is threatening to derail education development in Tanzania.

Data shows 31 districts in regions where nearly a third of children have been affected by malnutrition, their performances in the 2016 primary school leaving examinations (PSLE) were poor.

Chronic malnutrition affects the growth of children below the age of five, impairing their brains.

Nutritionists say children’s poor school performances and stunting are related.

They call on the government to improve the country’s nutrition status and ensure a good learning environment.

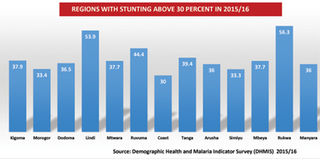

The Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16 data shows that the national average of severe malnutrition has slightly improved by 0.3 per cent from 34. 7 per cent in 2014.

But in some regions malnutrition levels are worrying. For example, in Mbeya malnutrition is increasing despite the region being among the top 10 food producers in the country.

Before Songwe Region was hived off Mbeya the malnutrition level was 36.5 per cent in 2014. But within two years, the undernourishment rate jumped to 37.7 per cent.

Although factors such as unequal distribution of teachers, poor learning environment and poor accountability between government and parents hinder the nation from attaining 80 per cent of pass rate in PSLE, stunting has not be overlooked.

In 2016, six districts in Mbeya had 60 per cent of pass rate in PSLE results, below the national target of 80 per cent.

According to National Examinations Council of Tanzania (Necta), Mbeya District’s performance in 2016 PSLE was at 54.18 per cent, Mbarali (53. 1 per cent), Chunya (51.8 per cent), Momba (40.85 per cent), Ileje (53.4 per cent) and Mbozi (56.7 per cent).

“Generally, our region is performing badly. Despite improving for three consecutive years, it has not attain the national target of 80 per cent,” Regional Consultative Committee 2016 report says.

Report adds that in 2014, when the national goal was to attain PSLE performance by 70 per cent, Mbeya achieved only by 48.89 per cent, becoming one the 10-worst performing regions for two years running.

Some experts say regions which have high levels of malnutrition are facing Mbeya’s plight.

In Dodoma, where 36.5 per cent of children under the age of five have been affected by acute malnutrition, its five districts scored below 60 per cent pass rate, according to 2016 PSLE results.

Dodoma’s Chamwino, Chemba, Mpwapwa, Kongwa and Bahi districts are indicated in the map by Necta that they performed below 60 per cent.

Although a report shows that Dodoma slightly reduced its malnutrition rate between 2014 and last year, it was among of 10 worst performing regions in PSLE in 2014 and 2015.

Morogoro primary schools also have a similar problem. Four of its districts scored below 60 per cent in PSLE despite the region being one of food baskets in Tanzania.

However, according to DHSMIS 2015-16 data Morogoro has slightly reduce the child malnutrition rate from 36.9 per cent in 2014 to 33.4 per cent in 2015.

Despite its improvement Morogoro, Mvomero, Kilosa and Kilombero districts also performed below 60 per cent in 2016 primary school examinations.

While some regions with high malnutrition levels perform poorly, pupils in Dar es Salaam where 14.6 per cent of children are stunted, scores in PSLE are high.

In 2015 PSLE results, Dar es Salaam was the best performing region with 83.17 per cent of pupils passing the exams followed by Kilimanjaro.

Kilimanjaro where the percentage of stunted children is below 30 per cent, the region’s pass rate was at 80.13 per cent in the same year.

Last year, the average pass rate in all districts in the two regions was above 70 per cent.

The Mbeya regional coordinator for reproductive health and child services, Ms Prisca Butuyuyu, agrees that malnutrition and pupils’ poor performances are related.

“Malnutrition results in the stunting of child. When it affects the growth of the child, they can be given supplements to boost the body but if the problem is not well handled while the child is below the age of two years, it can affect the brain development which is difficult to correct,” she says.

The severely malnourished child, according to her, can hardly learn. They are forgetful and cannot make decisions even when they grow up.

She called on parents to feed their children well to also improve learning.

Despite being among the largest food producers in country, children are underfed in Mbeya, resulting in stunting, regional nutrition officer Lewis Mahembe says.

The link between malnutrition and education performance is real. Last year, Twaweza, a non-governmental organisation, found a link between malnutrition and children learning after testing pupils aged between 10 and 14 in the ability to count and read a Standard Two story in English and Kiswahili.

According to the study, only 18 per cent of children who were severely malnourished were able to read in English. The same performance was demonstrated by moderately malnourished group of pupils.

The study shows that 65.8 per cent of well-nourished children were able to read in Kiswahili compared with 51 per cent of moderately malnourished group and 46.3 of malnourished.

According to the study that involved 197,451 children, 53.4 per cent of the well-nourished children were able to do a Standard Two multiplication assignment compared to only 37.7 per cent of moderately malnourished. The 35.5 per cent of severely malnourished children passed the same test.

Mr Ramon Lugome, a Songambele head teacher in Ludewa District, Njombe opines that nowadays parents spend much in education not because teachers do not teach well but because some pupils are slow learners.

He calls on parents to ensure that their children are fed well rather than paying a lot of money on tuitions.

“When children pass their exams, it is a relief to parents.”

Children can be rescued from future learning difficulties if parents invest in

If parents feed their children well, they can can even pass their exams with flying colours and grow up as healthy citizens.

Dr Neema Kimaro, of Dar es Salaam, advises mothers to breastfeed their babies for six months without supplements to avoid consequences of chronic malnutrition that causes mental retardation to children.

Dr Kimaro has advised fathers, the community and health workers to ensure that society become free from malnutrition.

The government understands the enormity of malnutrition.

Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre (TFNC) acting director Joyceline Kaganda says the government’s five -year plan is to reduce stunting from current 34.4 per cent to 28 per cent.

To attain that goal, the institution has been creating awareness on the important of consuming balanced diets.

“If we reach a time when society can demand nutrition as a basic right, then malnutrition will be reduced,” she says.

TFNC is also planning to include nutrition into the school curriculums, targeting adolescents who are future fathers and mothers to know the potential in human development.