Writing for Kiswahili language revolution

What you need to know:

‘Danger! Do not cross’ it said in English. He raises his eyebrows and asks with a bitter smile:

“What will they do if people don’t understand and get hurt?” he asks. “Road signs say ‘Diversion’ in English and not in Swahili. Why not in Swahili? We are a S

Words are not just words to novelist Enock Maregesi. Words are the bricks of our world and they have the power to change it, he believes. But words can also frustrate him. Recently he passed through Manzese in Dar es Salaam and noticed a written sign on the BRT lanes. ‘Danger! Do not cross’ it said in English. He raises his eyebrows and asks with a bitter smile:

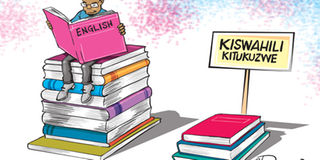

“What will they do if people don’t understand and get hurt?” he asks. “Road signs say ‘Diversion’ in English and not in Swahili. Why not in Swahili? We are a Swahili country. That is colonialism. We are being colonised without knowing it,” he says.

Enock Maregesi won second prize in Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature in November last year for his Swahili novel Kolonia Santita. He has always written in Swahili and he considers himself “a fighter” for his language. His debut novel Kolonia Santita is a crime fiction about a global drug cartel and is situated in a global sphere from Mexico to Paris, Mumbai, Cape Town and beyond. The title Kolonia Santita is the “Swahililised” Mexican name of the powerful drug cartel. He drafted the novel in 1992 aged 20, but it was not until 2012 that he published it after 18 years of additional research. In the years between he went to London and Manchester to study Networking and Creative Writing, and obtained a degree in Business Studies from the University of Wales in 2011.

Years back, as a secondary school student, he had found that he had a particular flair for words.

“I discovered that I had a passion for writing and I loved to be called ‘a novelist’. I even love it to this day,” he says.

Today his novel Kolonia Santita has more than 14,000 likes on Facebook and in August it will be republished by East African Publishers. However, Enock Maregesi’s passion is not only for storytelling even though he refers to the characters in his book as vividly as if they were seated next to him. His passion is with the Swahili language as well. In 1995 he pledged himself to fight for Swahili. He wanted to do something to “save Swahili.”

“I want to be an advocate for our language. Because people misuse it a lot. So we really have to fight for our language, because if we don’t have Swahili we will lose our identity,” he says.

This language “misuse” is not conducted by anyone in particular but conveys a general lack of appreciation of the language, he explains.

Instead of highlighting Swahili as an official language, it is pushed down on second place.

“People speak broken Swahili on purpose. Business people for instance will speak Sheng – a mixture of Swahili and English – because that’s what people want to hear. And what is the government doing? They speak broken Swahili most of the time. Swahili is getting lost and I am really sorry for the future generations,” he points out.

To counteract this “colonisation” of Swahili by English, Enock Maregesi has written all the 406 pages of his book with Swahili words. Even the countries are in Swahili.

Instead of ‘Nigeria’, he has written ‘Nijeria’. He acknowledges that this can seem as a minor detail and that people may find his mission close to ridiculous, however, he thinks that single letters and commas matter.

On the back cover of his book it says ‘This book is meant for a revolution of the Swahili language’. “It may take 50 years,” he says, “but it will come”.

“People think that other international languages are smarter and more business wise. But they have to understand that we have to preserve our culture.

We need to have our own identity,” he says. Swahili is not the only language that must be handled with care he points out, and refers to his other language, Jita, from Mara Region where he grew up.

Enock Maregesi’s encounters with other people who praised their language made him wonder why he could not find the same praise for Swahili at home. At the same time he found inspiration in other people’s love for their languages. “An Indian child is brought up in England, and he will speak both English and Hindi very well. English in school and Hindi at home. But here it’s English both in schools and at home. Why can’t you speak Swahili with your child at home? If this continues we will turn into an English speaking country,” he says.

Novelists and the literary world play an important part in shaping languages, Enock Maregesi believes. The Swahili they write influence the readers and their languages. The literary obstacle in Tanzania is not that people do not read, he points out, but that they “don’t read because there are no interesting writers,” as he puts it.

He is currently researching for his new book which is mainly set in Dar es Salaam but with a global view as well.

His novels are set in a global space and pace; however, he has never visited most of the places. He wrote his first book in London but the story took the reader to places in Mexico, Denmark and India, and carefully avoided London.

He accesses these global locations with his feet planted in front of his computer, he explains. He will use his Internet connection to carefully enter the streets of a foreign city and find out how long it will take his main character to get from the airport to the city centre – and if there are any shortcuts on the way.

“I wanted to do something new,” he says. “The world is becoming a global village and we have to understand these different cultures. There is a Danish culture, an Israeli culture and so on. So if you want to go to Denmark, then read the book,” he says.