Soundtrack of Pains and Joys of Growing Up

What you need to know:

As a personal trick to help me focus and speed-read, I normally put a semi-decent song on auto-repeat in the background.

It is 1:13am, everyone is sleeping and I am reading a dense draft report of a Task Force my ministry had launched a few weeks earlier to examine the environmental degradation of the Great Ruaha River ecological system.

As a personal trick to help me focus and speed-read, I normally put a semi-decent song on auto-repeat in the background.

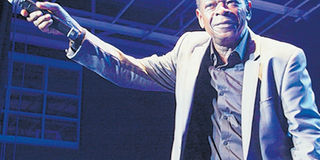

But today it is not working. I made the wrong choice in picking as background noise Sam Mangwana’s ‘Bana ba Cameroun’ from his famous ‘Maria Tebbo’ album.

The rich, weathered tenor of this African journeyman refused to be my mental monotone. And for a good reason too. And who was I fooling to attempt this?

The album – with other hits such as ‘Tchimurenga Zimbabwe’ – popular in the 1980s, defined an era for Africa: of innocence, of hope, and confusion.

People of my generation were adolescents when this song was popular, coming of age and becoming clearly conscious of the morality of our parents’ and leaders’ choices and aware of the moral compromises they made – either for our future or for their own indulgence.

We saw adults conveniently but temporarily escaping not only from their fears but also their sins through these melodies.

So, as I struggled to read my report, Sam Mangwana refused to let me concentrate; he chose to speak to me instead.

Not through lyrics of course (because I don’t understand the words), but through memory that the melodies has imprinted in me over the past 30 years.

We grew up with these songs - and they form the soundtracks of pains and joys of growing up.

In the melodies, arrangement, composition, tempo – everything that makes this album – you can’t miss the optimism, the innocence, the naiveté, and the spirit of 1980s Africa. Above all, as a discriminating consumer of music, you can’t remain focused on anything else, as I foolishly attempted, when the croon is this smooth, breathy, almost liquid in quality.

For me, only three Congolese singers – Nyboma, the late Papa Wemba and Sam Mangwana – can hit magical notes capable of “transporting” you to Valhalla.

Perhaps I couldn’t focus because there is a moral to the Sam Mangwana story that has stuck with me throughout the years.

As a teenager, he sprang into the spotlight, with heavy expectations, as a lead singer at Africa Fiesta next to Rochereau, a giant already in 1963. He didn’t last long at Africa Fiesta, he moved on to start his own band, then moving from one band to another.

In 1960s and 1970s musical and social scene in Congo, you were either with Franco or Rochereau, not both.

Not to Sam Mangwana. In 1972, he jumped to TP OK Jazz, defying the myth of “ideological purity” between the Franco-Rochereau camps.

For a number of months, to avoid harm from angry Rochereau fans, he had to hide and remain under police guard.

He sang some great numbers with TP OK Jazz before again taking off: moving to Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroun, Togo and finally Ivory Coast, where he tried to settle with a new band, called Amida.

It didn’t work out either; the band fell apart. He tried again and formed a new band – The African All Stars – with some good number of stars, including at varying points Lokassa Ya Mbongo, Nyboma, and his cousin Syran Mbenza.

This group is the one that produced Maria Tebbo, the album that I am still playing, now no-longer-in-the-background. Predictably, the group collapsed and Sam Mangwana has kept travelling.

Up to this date. As a mega-star in the Congo, it has been written that he never owned a place of aboard.

Never settled down. Does not have a solid band. He is now 72. He burst into the scene in 1963 as a talented and fearless teenage lead singer of a major band.

Now he performs at inauspicious venues such as Manyatta Club in Oakland, California.

His story is that of Africa: a dream deferred, a flickering star on the verge of dimming or shining, anxious about a sense of our place in history, indeed our immortality.

Perhaps I could not concentrate because of Syran Mbenza who, for me, forget Carlos Santana, forget Ali Farka Toure, is the greatest living guitarist; indeed a true heir of Franco’s guitar (Andy Kershaw, the great BBC music commentator once said “Eric Clapton isn’t fit to tune the strings of Syran Mbenza”).

In Bana ba Cameroun, Syran effortlessly manipulates the lead solo with his clearly plucked two-finger sparkling riff, creating a lush melody with spirited yet laid-back tempi and simple yet weaved repetitions that egg Mangwana and the entire band on.

May be I couldn’t concentrate because the melodies simply triggered a subconscious trauma in me of Africa’s unfulfilled promise.

Just listen to ‘Tchimurenga Zimbabwe’, released to celebrate Zimbabwe’s independence, and think of Zimbabwe and Sam Mangwana today.

Perhaps trauma is the correct feeling to allow reflection. And perhaps music is successful when it does this.

But not to worry for Africa has a new sound – noisier and with an urgent tempo – that is recording and defining a new era: no longer of innocence, but still of hope and confusion.

Anyway. Back to reading the Ruaha report, with a new semi-decent song: Iris by Goo Goo Dolls. Wish me luck