SPECIAL REPORT: Pupils stare at bleak future in skewed teacher allocation plan

What you need to know:

The government, which has announced that it would recruit over 40,000 teachers, faces a Herculean task to address the disparities that have had a hard-hitting impact on schools in rural areas.

Dar es Salaam. Public primary schools in rural areas, still battling with an acute shortage of teachers, may have to wait a little longer for relief, official data that reveals the glaring uneven distribution of teaching staff across the country suggests.

The government, which has announced that it would recruit over 40,000 teachers, faces a Herculean task to address the disparities that have had a hard-hitting impact on schools in rural areas.

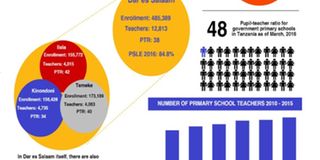

A recent analysis by The Citizen of dataset dubbed ‘Pupil to Teacher Ratio in Government Primary schools in 2016’ as of March last year, reveals that some regions with low enrollment have more teachers than those with the highest number of pupils.

It’s a contradiction that has, for years, created unequal learning opportunities between pupils in state-run schools in Kilimanjaro, Arusha and Dar es Salaam, who have adequate teachers, and their counterparts in Kigoma, Mara, Mwanza and Rukwa where there are critical shortages of teaching staff.

Data from the government’s open data portal, which The Citizen verified through physical visits to selected schools in these regions, reveals that inequality in teacher distribution plays a major role in academic performance, with disadvantaged areas doing badly in the Standard 7 national exams.

Even in cities where the majority teachers prefer to live, there is still glaring inconsistency in how teachers are distributed with Arusha having more numbers than Dar es Salaam, Mbeya, Tanga and Mwanza.

For example, Dar es Salaam had 485,389 pupils and 12, 813 teachers, almost the same number with Mwanza, which had 627,695 pupils. Mwanza, which had 142,306 more pupils than Dar es Salaam, had 12,833 teachers only.

With a total enrollment of 333,601 pupils in primary schools by March last year, Simiyu Region had 71,484 more pupils than Arusha (262,117 pupils), but it had only 7,093 teachers, while the latter had 7,605 teachers, according to the data. This means Arusha had 500 more teachers than Simiyu despite having a relatively low enrollment.

The pupil-teacher ratio (PTR) in Simiyu stood at 52 against Arusha’s 37, making it one of the 10 regions with the lowest number of teachers. And while more than half of public primary schools in Ruvuma have pupil-teacher ratio above the normal standard of one teacher for 40 pupils, in Kilimanjaro, more than three quarters of the schools enjoy the best PTR.

Data shows that Kilimanjaro with 253,263 pupils had 8,279 teachers, about 1,962 more than Ruvuma with a larger number of pupils. Ruvuma, a south western region with a PTR of 47, had a total enrollment of 271,701, but had 6,341 teachers only.

Though it has been claimed that the availability of teachers alone does not guarantee quality of education, Dar es Salaam, Kilimanjaro and Arusha, which top all the regions in numbers of teachers, have been performing well in the past Primary School Leaving Exams (PSLE).

The three regions have been clinching top 10 positions almost every year, including 2016, while regions like Kigoma, Dodoma and Tabora lag behind.

Generally, Tanzania has persistently faced a serious shortage of teachers in both primary and secondary public schools, particularly for science and mathematics subjects.

By the end of December last year, according to data obtained by The Citizen from the President’s Office, Regional Administration and Local government, the nation was short of 47,151 teachers for public primary schools. That may be a conservative figure – the situation could be worse, independent sources of data suggest.

A 2014 report by the United Nations education agency (Unesco)’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Education for all Global Monitoring report, says Tanzania needs to recruit at least 406,600 new teachers by 2030. This translates to an average of 25,412 teachers’ recruitment annually from back then.

The reason for higher numbers of teachers in urban schools is a no-brainer. Rural schools lack the basic facilities that can attract even an average, less-experienced teacher.

Most run with no classrooms, no desks and chairs, no clean and safe water, and no decent houses for teachers. Getting to some of the schools in remote areas is a nightmare. There are no proper roads, no electricity. Teachers are forced to walk for hours to the nearest town.

If they are to use bodaboda to the nearest bus stops, they have to dig deeper into their pockets – despite the fact their monthly salaries are hardly enough for basics.

In some regions, where The Citizen visited recently, a teacher has to build his own grass-thatched mud house on arrival because there are no houses – not even to rent. In short, the working environment is pathetic and unbearable. For those who have endured over the years, it’s been a life of sacrifice all the way.

At Chohero Primary School in the Mvomero District of Morogoro, for instance, the two teachers who handle 510 pupils walk almost 20 kilometres to the nearest bus stop. Last year, only six out of the 49 Standard 7 pupils who sat the PSLE passed with an average of C.

In an interview with The Citizen, Kigoma Regional Education Officer Omari Mkombole said the uneven distribution of teachers was a direct result of the difficult life in most rural areas. Teachers who quit join private schools in town.

“If the government provides more incentives for teachers they may be motivated to teach in rural areas. In Kigoma, we will prepare our own package to retain teachers; directives have already been sent to all District Commissioners,” he said.

Government position

Mr Juma Kaponda, the director of education management in the President’s Office (Regional Administration and Local government), says the disparity in distribution is due to a number of reasons, but mainly health and social factors affecting teachers. Married couples prefer working in the same area, and there are teachers with health complications – these would want to be close to hospitals.

But Mr Kaponda admitted that the disparities had proven costly, and the government was working on rectifying them. “Teachers in areas with critical shortages are being overworked, reducing their efficiency and producing poor results,” he says.

“Directives have already been issued to municipal councils to ensure that they re-allocate teachers to fill gaps in those areas facing scarcity. Also, this year the government will employ 40,000 teachers for primary and 10,169 science and mathematics teachers for secondary schools to fill the gap,” adds Mr Kaponda.

For education experts, the disparity betrays the absence of a clear policy on incentives for teachers living in harsh environments. Dr Luka Mkonongwa, a lecturer at the Dar es Salaam University College of Education (Duce), reveals just how bad the situation can be. “Due to poor working conditions in many rural areas some teachers are forced to lie that they are suffering from certain diseases in order to be transferred,” he says.

He also says the opportunity to relocate due to marriage is also leaving some female teachers with no option but accepting marriage proposals only from men living in towns.

“It’s very difficult to block transfers where marriage or sickness is cited as the reason for a request. Therefore, there is no long or short term measure that can solve this problem without investing in better social services across the country, and providing special incentives to teachers living in rural areas.”

In our special education report tomorrow: The touching tale of a school with 510 pupils and only two teachers