The challenge of building ‘New Gambia’ after Jammeh’s fall

What you need to know:

- It has been a head-spinning few days for the nation as it breaks free from oppression to rebuild what the incoming coalition government, headed by Adama Barrow, has branded “New Gambia”.

Last Friday, the unbelievable happened in Gambia: after 22 years of autocratic rule, Yahya Jammeh (pictured) peacefully conceded defeat in a historic presidential election. By Monday, 19 political prisoners, including former opposition leader Ousainou Darboe, had been released from jail.

It has been a head-spinning few days for the nation as it breaks free from oppression to rebuild what the incoming coalition government, headed by Adama Barrow, has branded “New Gambia”.

The challenges ahead are daunting. Ensuring a safe transfer of power and reassuring the country that the new government has a strong reform plan are the immediate tasks.

But after more than two decades of misrule, Gambians are also impatient for change and the list of problems is long: a prostrate and undiversified economy, a high rate of outmigration, heavily politicised state institutions – including a military and a criminal justice system used to operating by fear.

Expectations are sky-high as so much already seems to have happened so quickly.

Coalition 2016, officially formed only one month before the election, swept to victory on Friday with 46 per cent of the vote, to Jammeh’s 37 per cent. Independent candidate Mama Kandeh trailed on 18 per cent.

Soon after the announcement that Jammeh was to stand down, delivered by the reportedly trembling chair of the Independent Electoral Commission, Gambians began pouring onto the streets, shouting for joy and dancing as car horns wailed.

The jubilant scenes shared through social media were a collective release. “It was like we had been under a magician’s spell and the spell had just broken,” said Alieu Bah, a 24-year-old activist and writer.

“Twenty four hours earlier we were in the polar opposite situation. It was like a dream. No one saw this coming, even the most optimistic of people.”

The coalition’s popularity was no surprise. Its two weeks of electoral campaigning had culminated in youthful and energised crowds packing streets for several kilometres in the rallies held in the urban coastal areas. But nobody expected Jammeh, who had vowed that only God could remove him from power, to accept defeat without a fight.

“People were ready for change, but knowing the type of person Jammeh is, they did not believe that he would concede defeat without contesting the results,” said exiled journalist Alhagie Jobe, reporting from Dakar, Senegal. “Hopes were not high for a peaceful transfer of power.”

Gambians were bracing for the worst after Jammeh, without warning, imposed a total internet and telecommunications ban at 8pm on the eve of the election. “We thought there would be Ivory Coast-style electoral violence,” said Jobe, referring to a 2010-11 crisis that led to civilian massacres.

But the communications blackout ultimately failed to intimidate voters, and activists and journalists within the country published rolling results via SMS and on satellite phones, in a victory for transparency.

“Jammeh was not happy,” said Jobe, who had been tortured and imprisoned for 18 months by the regime. “He fought behind the scenes. He did all he could to hold on to power, but because there was such a strong atmosphere for change he knew he couldn’t stop it: the people had spoken.”

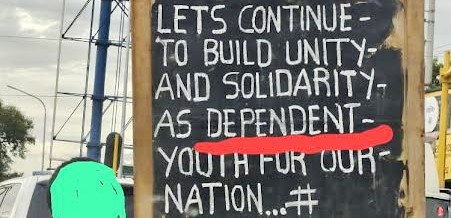

There are now great hopes – and pressures – on the coalition to deliver their promise of a New Gambia, especially among youths who voted for change in unprecedented numbers.

“Youths came out and voted in this election and their voices have been heard,” said Dakar-based rapper Jerreh Badjie (stage name Retsam).

Youth activist Mariama Saine said she hoped that once the new government took back all the industries owned by Jammeh, including farms and factories, there would be more employment opportunities that would provide an alternative to high-risk migration.

“Jammeh has monopolised any sector youths could fit into, now these will be areas the new government can develop for youths.”

For Bah, a new referendum should be held on the constitution to guarantee the secular nature of the country, introduce term limits, and guarantee human rights, and freedom of movement.

“Jammeh also needs to be held to account,” he said. “He should face justice through a fair trial.”

Bintou Kamara, a Paris-based Gambian who founded an organisation to disseminate information about migration, said: “Now, there is a new window of hope for the entire population.

“Some migrants I have spoken to who are in a deplorable situation in Europe are thinking of going home. They will be empty-handed but they will be coming back to hope. There will be lots of returnees.”

The most immediate change for Gambians is the ability to speak freely. Over the weekend, the scenes from former businessman Barrow’s victory parade showed partying crowds and people tearing down and stamping on Jammeh’s paternally smiling election banners.

Bah, one of the few activists to criticise the government through social media while living in Gambia, told IRIN that before the election he could have been arrested at any time. “People really feared for my life, but I survived. This is what it means to triumph over a dictatorship. Gambia has become a beacon of hope. This is what we want to be remembered for.”

The writer is a freelance journalist and regular IRIN contributor