Prime

Billionaires, media and society: Who really shapes your vote?

Every election season has its stars. Not the candidates on stage, but the quieter forces in the wings: the billionaire men who can tilt the game, the media that tells the story, and the community that decides whether to believe it. Together, they form an unspoken triangle of influence a power play that shapes how democracies breathe, both globally and here in Africa.

Globally, over 11 percent of the world’s more than 2,000 billionaires have stepped directly into politics and when they run, they win 80 percent of the time. In China, where political-business ties are even tighter, 36 percent of billionaires hold public office. The rest don’t need to run for anything. Their influence comes through money. In the US, just 50 billionaire families poured over $600 million into the 2024 elections by mid-year. By November, 150 billionaire families had spent nearly $1.9 billion, eclipsing the $1.2 billion spent by 600 individual billionaires in the 2020 cycle. Globally, elections are becoming high-stakes investments the 2024 US campaign alone is projected to hit $20 billion, with $16 billion of that on ads.

Africa is no stranger to concentrated wealth. Four billionaires hold more wealth than the continent’s poorest 750 million people combined. In the past five years, Africa’s 23 billionaires have grown their fortunes by 56 percent, now totaling $112.6 billion. Most of this wealth is concentrated in South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya, and Morocco, which account for over 90 percent of the continent’s billionaires. And yet, fewer than half still live on African soil a reminder that money moves faster than patriotism.

In an ideal world, the media is the referee in the political game blowing the whistle when rules are broken, calling out fouls, and keeping the match fair. But when billionaires own the referees, neutrality is harder to guarantee. Globally, media ownership by billionaires is not rare from Jeff Bezos with The Washington Post to Rupert Murdoch’s vast empire. Ownership gives not just prestige, but agenda-setting power: the ability to decide which stories lead, which voices are amplified, and which angles are softened. In Africa, similar patterns emerge. In South Africa, four dominant groups including Naspers (via Media24) and Remgro control 88 percent of the print market. In the run-up to the 2024 elections there, political donations reached a record R172 million, with billionaire-linked entities among the biggest givers. Patrice Motsepe’s companies, the Oppenheimers, and Naspers all backed major parties investments that may shape not just political fortunes, but also media narratives.

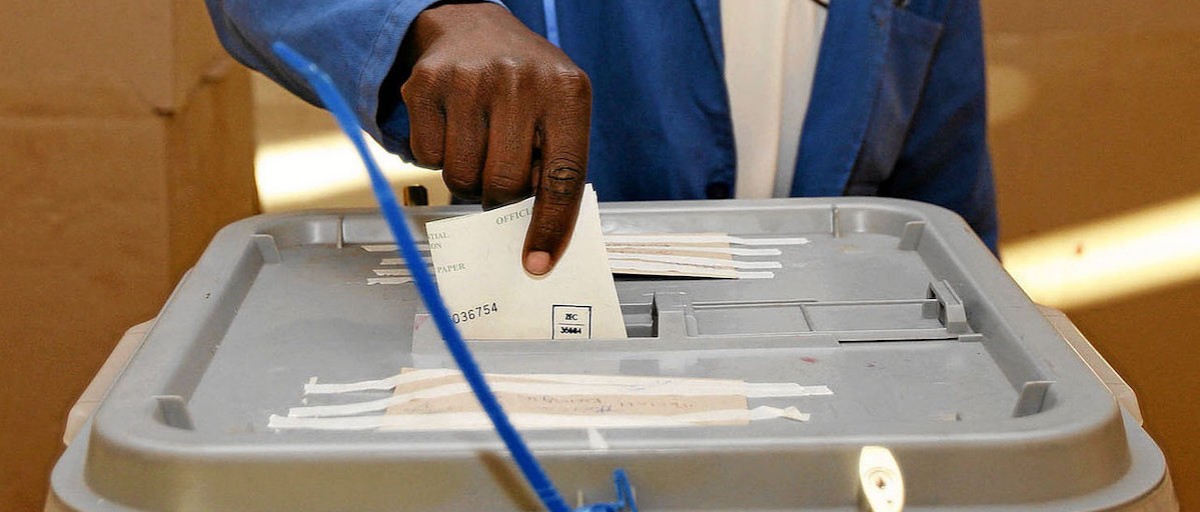

The community millions of everyday voters stands at the end of this influence chain. In the best-case scenario, they use information to make informed choices, rejecting spin for substance. In the worst case, they are overwhelmed by noise, seduced by well-timed philanthropy, or numbed by repetitive messaging. Across Africa, elections are expensive undertakings. On average, they cost $4.20 per capita nearly twice the global average. Between 2000 and 2018, sub-Saharan Africa spent close to $50 billion on elections. That’s money that could build schools, hospitals, or infrastructure but instead funds the ritual of democracy, often with questionable returns on public trust. Communities now have more tools than ever from WhatsApp groups to TikTok activism to fact-check, mobilise, and push back against biased coverage. But these same channels are ripe for manipulation, with billionaire-funded narratives able to dominate feeds overnight.

As we enter the thick of election season, the billionaire–media–community dance intensifies. Money will flow, headlines will compete, and narratives will be crafted with surgical precision. The risk is that, in this noise, the real issues jobs, healthcare, education, and cost of living get drowned out by personality politics and spectacle. The truth is, billionaires are not always villains, and the media is not always biased. Many wealthy figures fund real development. Many journalists risk careers and safety to hold power to account. But influence without scrutiny is dangerous. And communities that stop asking hard questions lose their strongest bargaining chip.

In this pre-election moment, every voter should pause and ask: whose story am I hearing? Who benefits if I believe it? Is this information, or is it influence? Because the most powerful player in this triangle is not the billionaire or the broadcaster. It is the community that decides when the music stops. Your vote is your microphone. Use it to make your own headline.

Angel Navuri is Head of Advertising, Partnerships and Events at Mwananchi Communications Limited