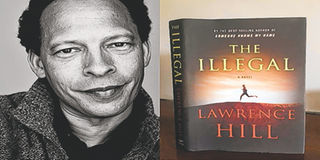

MEET THE AUTHOR : Lawrence Hill and the illegal race to victory

Author Lawrence Hill. PHOTO I COURTESY

What you need to know:

- All Ali has ever wanted to do is to run — run as a marathon champion to fulfil his childhood dreams and to bring glory to his first coach, his father. As it turns out, Ali has to make several other runs, including a sneaky escape from Zantoroland to save his own life.

The Illegal is the story of a refugee marathon runner, Keita Ali. He is a 25 year-old native of a volatile fictional country known as Zantoroland, where the ruling class routinely unleashes repressive acts that will be familiar to anyone who has paid close attention to debates on human rights violations worldwide.

All Ali has ever wanted to do is to run — run as a marathon champion to fulfil his childhood dreams and to bring glory to his first coach, his father. As it turns out, Ali has to make several other runs, including a sneaky escape from Zantoroland to save his own life.

In the fictional Freedom State, where he finds refuge, Ali encounters racial discrimination. Now, he must find ways to flee the closing net of the immigration department. Ironically, it is in this place of historic exclusion that Ali stands better chances of shining on the international stage because the locals are poor runners despite the fact that the super-wealthy Zantoroland has superior training facilities (echoes of the dilemma of Kenyan-born Bahraini runners, anyone?).

Ali is challenged on many fronts. He is running from mercenary athletics agents and against friendly Americans and “second-tier runners from Kenya, Ethiopia and Zantoroland”. His performance is hampered by his failing health and sketchy living conditions. At some point, he goes into hiding in AfricTown, a low-income neighbourhood where most of the 100,000 undocumented people live in 15,000 used shipping containers.

How will Ali remain hidden in this slum and simultaneously train out in the open for upcoming marathon competitions? He desperately needs the prize money from these competitions to attend to his ill health and to save yet another life back in Zantoroland because the tyrants in his homeland see no shame in demanding ransom money from a refugee.

AfricTown is a profile of heartlessness; a study of the ways in which ordinary people succeed despite unnecessary bureaucratic obstacles.

Keita Ali snatches many victories in the face of looming threats. His successes are aided by some unlikely accomplices. They include a liberal 85-year old white woman; a senior policewoman who dabbles as a marathoner; Lula DiStefano “the unofficial queen of AfricTown”; Viola, the “unassailable black, gay and disabled” journalist and John Falconer, the whiz kid from the slum who films everything around him — sometimes secretly — eager to make a documentary about Africtown.

All the while, the messages from Zantoroland are intimidating – kidnappings, murder, deportations and ransoms. These messages cloud Keita Ali’s mind. They distract him during his stealthy training sessions in the park and on the open road. They provide him with the motivation to run and win.

The tendency to sketch journalistic summaries of action suggests that Hill does not have his pulse on the dynamics of military coups and failing states. He makes up for this weakness by exploring the mind of a race champion with piercing attention.

Keeping me awake for the Rio Olympics, Hill’s account of a fictional runner’s training life was, to me, all the more striking for its diligent details about a runner’s diet; training schedules; race tactics; performance anxieties; contracts and costumes — especially the shoes.

There is a near-fetish status given to the portrayal of running shoes. The 10-year-old Keita Ali treats his shoes as his most prized possession. They are invariably referred to by their brand name — “he was so in love with his Meb Supremes”.

During training or in the middle of a marathon, Ali takes note of a competitor’s shoes to appraise his abilities – “the lithe runner meant business. No socks in his racing shoes. An easy, smooth gait. Arms pumping efficiently. Keita couldn’t hear his breath”. The quality of shoes and the way they are worn, sets serious runners apart from mere beginners.

Shoes become a symbol of freedom. They enable swift flight when government agents raid AfricTown. On the streets of Clarkson city, the right shoes can lend unwanted people of colour, a measure of acceptance. John Falconer, the young genius from AfricTown, might not be a runner, but he wears running shoes to the prize-giving luncheon for the Best Essay Written by High School Students in Freedom State. The running shoes function as a statement of his intent to rise above the circumstances of his birth.

I thought this novel would delve into the politics of religion, given the protagonist’s Muslim surname. Instead, it is the politics of race and the economy of road racing that lie at the heart of The Illegal. The secrets to Lawrence Hill’s captivating capacity to explore these two meanings of the word “race” can be found at the very end of the book — in the Acknowledgements pages.

One of these secrets should offer new and exciting vistas for all those Kenyans who spend many years fighting stiff local competition in the hope of becoming road-race champions. There is another way to expend all of that knowledge about competitive running and Hill exemplifies it.

On that note, I am privy to the news that when Kenya hosts the World Youth Championships next year, we will celebrate the sacrifices and achievements of our runners with a stunning in-depth book by Jackie Lebo, that tireless documentary filmmaker who heads Content House Initiative. It is titled Running: The Story of Kenyan Maestros. I can’t wait.