Prime

Books and beyond: How one initiative is shaping young minds

What you need to know:

- The programme’s blend of storytelling, moral lessons, and interactive games has worked wonders—especially for children who previously struggled with concentration or comprehension.

- When a child acts out a story they’ve just read or begins questioning a character’s choices, it’s a sign that something is shifting in their thinking. It’s the beginning of a foundation they’ll continue to build on well into adulthood.

The bell had just rung at Grace Pre and Primary School in Sinza, but rather than rushing to the playground, a group of pupils huddled around a collection of books on a worn-out mat beneath a mango tree.

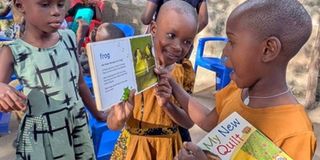

Their eyes scanned each page, lips moving softly in rhythm with the printed words. One clutched a story about a lion cub who learnt how to overcome fear. Another giggled while reading a short riddle in an English puzzle book.

It wasn’t a typical school-day routine. I had come to witness firsthand how a small idea, born out of a humble reading club, had evolved into a registered, full-fledged initiative with a mission to restore the reading culture in Tanzania—starting with the youngest minds.

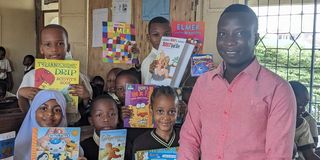

Lameck Bagumya with pupils from Grace Pre and Primary School. PHOTO I COURTESY

The Bright Hope Reading Initiative (BHRI), officially registered under the Ministry of Community Development, Gender, Women and Special Groups on April 25, 2024, is already making visible strides. With legal authorisation to operate across mainland Tanzania for ten years, the initiative is implementing its programmes with growing energy and ambition. BHRI’s impact lies not in its size or budget, but in its sincerity, consistency, and ability to touch lives where it matters most.

Mr Peter Mwansasu, a teacher at Grace Pre and Primary School, says he never used to read anything beyond what was required for class. But ever since BHRI came to the school, it has helped him grow as well. “Now I find myself reading children’s books not just to teach but for my own enjoyment.”

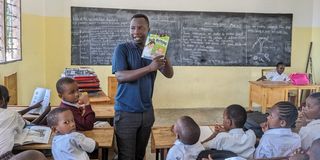

According to him, the initiative has brought a fresh rhythm to the school routine. Students now look forward to reading sessions, which take place twice a week. On those days, attendance noticeably increases and the energy around the school shifts.

“They know it’s reading day, and they don’t want to miss it. They’ve started to read not just for grades but for the joy of discovering something new,” Mr Mwansasu tells me.

The school’s headteacher, Mr William Silla, believes the programme came at the right time. “We’re in a generation where children are lured by screens more than books. Without something like this, most of them would grow up knowing what happened in a video game but not understanding the consequences of real-life decisions because they’ve stopped reading. Knowledge is locked inside books, and many children have thrown away the key.”

Mr Silla says the programme’s blend of storytelling, moral lessons, and interactive games has worked wonders—especially for children who previously struggled with concentration or comprehension.

“When you see a child act out a story they’ve just read or ask questions about characters’ choices, you know something is changing in their thinking. It’s laying a foundation that they will build on even in adulthood.”

The idea, according to BHRI founder and chairperson Lameck Bagumya, was born out of observing that few people—whether in rural villages or urban centres—read outside the demands of formal education.

What began in 2021 as a small reading club has since grown into an organisation aimed at countering what Bagumya describes as 'a slow erosion of intellectual curiosity among young people.'

Bagumya says if children learn to enjoy reading early, they will grow into adults who think critically, act ethically, and contribute meaningfully to national development.

We chose to begin where it matters most—at the grassroots—because the earlier a child starts to read, the deeper their roots grow in knowledge,” he says. In its six-month pilot phase, BHRI visited ten primary schools—half private, half public—as well as three tuition centres and two orphanage centres. At each school, they ran 40-minute reading sessions twice a week, incorporating games, role play, and group reading.

“We don’t just hand them books. We sit with them, read with them, talk about the stories, and act them out. The goal is not to memorise but to internalise,” he explains.

Eight-year-old Jonathan Mboya shares how the reading initiative has transformed his school experience.

“The initiative has helped improve my English and Kiswahili. It has also encouraged children to study hard. We are grateful for this and thank our teachers for teaching us how to read.”

Another pupil, nine-year-old Amina Mtoro, says the programme has helped her learn about different cultures from around the world. “It has enabled me to learn about people in different countries and understand their way of life. I’ve been reading a lot since then,” she shares.

The programme extends beyond schools. Through a door-to-door outreach approach, BHRI engages with families in various communities, offering parents tips on how to encourage reading at home. Bagumya says this approach has led to a shift in some households, with parents reading aloud to younger children before bedtime and encouraging older ones to read daily.

Selecting appropriate books has been crucial. The team curates materials based on the child’s age, school level, and reading ability. Picture books with minimal text are given to younger children, while older pupils receive moral tales and brain-teaser stories designed to sharpen their reasoning skills.

The books come from several sources. Local partners like Room to Read have been instrumental. International donors such as Australian Books for Children of Africa and authors Leslie Mitchell, Andrea Hyatt, and Emma Mactaggart of the International Read to Me Day have also shipped titles from abroad. However, every book must pass through the Tanzanian education quality authority to ensure cultural relevance and language appropriateness.

Despite limited resources, BHRI has also embraced digital reading. With donor support, it acquired a projector, now used to show animated stories at Grace Pre and Primary School, making reading sessions even more engaging. Some students have even participated in international reading exchanges with peers in Japan, the US, and Australia, where they share stories, cultural lessons, and personal reflections.

Of course, the journey has not been without its challenges. There remains a significant shortage of Kiswahili storybooks with appropriate content for children. Many parents still underestimate the importance of reading in a child’s development, and some schools, especially in rural areas, lack the technological infrastructure to implement digital reading sessions.

Transportation and funding also limit BHRI’s reach. “We’d love to expand faster, but costs remain a barrier. Travelling to remote schools, printing storybooks, training teachers—it all adds up,” says Bagumya.

Still, the team is not short on ambition. Future plans include extending the programme to other regions. BHRI also intends to launch mobile libraries, conduct regular teacher-parent training sessions, and collaborate with local publishers to create high-quality Kiswahili storybooks.

Perhaps most exciting is the plan to build a dedicated reading hub—a physical space where children can walk in, borrow books, read, and interact with trained facilitators.

“We want to create a place that feels like a second home for young readers. A place where reading is not viewed as a punishment but a celebration,” says Bagumya.

As I left Grace Pre and Primary School, I watched a group of children pass around a short storybook titled Maua ya Tumaini. They were sitting shoulder to shoulder, whispering sentences to each other—sometimes laughing, sometimes pausing to think. None of them looked bored or distracted. This reminded me of something Mr Mwansasu had said earlier: “If we want a generation that asks questions, solves problems, and leads this nation into a better future, then we must put books in their hands today.”

And if what I saw is anything to go by, then perhaps the future of Tanzania is already quietly turning its pages.