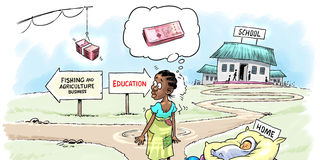

How income-generating activities hinder school re-entry in Muleba

What you need to know:

- Drawn by the allure of instant financial independence, scores of children, both boys and girls, are tempted to leave school to venture into self-employment

Muleba. The presence of income-generating activities, such as fishing and agriculture, in Muleba district council has become a double-edged sword, one that holds the key to immediate income while simultaneously hindering the dreams and aspirations of youngsters.

In this district, where lush farmlands and abundant agricultural produce dominate the landscape, a heart-wrenching dilemma plagues the young minds of teenage mothers and girls.

Income-generating activities, such as fishing and agriculture, offer the promise of financial stability but, paradoxically, are luring teenagers away from the pursuit of education.

This is a stark reality for many teens, especially girls, like Sophia Ndibalema*, a 21-year-old mother of two. Sophia's story mirrors the challenges faced by numerous young women in the district.

Sophia got pregnant with her first child while still a student and the burden of economic necessity forced her to make a difficult choice.

She reflects on her decision with regret, realising that she lost a valuable opportunity for education. Sophia's story is not unique. In Muleba District, scores of children, both girls and boys, are drawn by the allure of immediate financial independence and tempted to leave school to venture into self-employment.

This has led to a high rate of school dropouts in the district, predominantly attributed to economic pressures.

For example, at an undisclosed secondary school in the district, the head teacher reports that over 60 students drop out annually due to poverty. These students opt for income-generating activities such as fishing, agriculture, and, in some unfortunate cases, early marriage.

Most find themselves trapped in a vicious cycle of financial struggle, a cycle that seems difficult to break.

One of the key attractions for young people in Muleba is the district's abundance of crops with immense economic potential, including green bananas, coffee, beans, cotton, cassava, and tea.

Many girls aged 10 to 20 opt to engage in farming and fishing, believing that these endeavours can secure a better future.

Halima Mdoe's story exemplifies the allure of these economic activities. She decided to drop out of school to manage her green banana farm since she was already earning money while attending school.

However, her life took an unexpected turn when she got pregnant six months after leaving school.

Her partner, a young fisherman, abandoned her a few months later, leaving her with a child.

Her parents refused to help her raise the child so she could return to school when the opportunity arose.

The situation in Muleba has significant implications for education in the country.

Education is not just a personal aspiration but a tool for societal and national development.

High drop out rate

Government data for 2022 revealed that a total of 329,918 students dropped out of school, with boys accounting for the largest share of dropouts, about 55.2 percent.

In Muleba district alone, 2,955 primary school pupils and a staggering 4,210 secondary school students dropped out.

The presence of income-generating activities in the district poses a significant threat to the educational pursuits of the younger generation.

Kagera Regional Commissioner, Ms Fatma Mwassa, emphasised that over 16,000 primary school pupils and 6,700 secondary school students dropped out in 2022.

At Kishoju Secondary School in Magata/Karutanga ward, only 164 out of 197 students registered to sit for this year's Certificate of Secondary Education Examination (CSEE) were ready to write the exam.

At least 33 students have gone missing, according to the head teacher, Mr Peter Lyakulwa.

While Education Circular No. 2 of 2021, which is the government's policy allowing school re-entry for dropouts, is commendable, the formidable challenges facing those who left school due to economic pressures are undermining it.

Among other guidelines, the circular specifies that students will return to school within two years after dropping out.

Also, the school leadership is required to call a joint meeting between the parents or guardians and the school board to discuss how to help the student in question.

However, the reality on the ground is far more complex. As Mr Ayubu Msomera, a resident of Muleba rural, points out; “It is challenging to persuade young girls to return to school when they see their peers who dropped out continuing their lives in agriculture and fish farming.” Msomera's daughter, like many others, is torn between education and immediate financial independence.

A recent survey by the Msichana Initiative, an organisation advocating for the right to education for girls in Tanzania, shows a series of challenges faced by teenage mothers and students.

The survey aimed to collect and compile data on the views of different stakeholders on re-entry guidelines and how they should be implemented at the local, regional, and national levels.

It is intended to provide a basis for strong evidence-based policy advocacy on the re-entry of schoolgirls.

The study revealed that eight out of 10 girls who got pregnant, and 85 percent, wish to go back to school. The remaining 15 percent need more time to create an enabling environment for them and their children so that they can study without encountering obstacles, including mental stress.

Some of the girls in Muleba choose to seek knowledge outside the formal education system because they believe that going back to school is a waste of time and that it's better to get training or engage in other activities that will enable them to earn a living for their families and children within a short time.

Education is a fundamental human right, and its impact extends beyond individual aspirations. It plays a pivotal role in societal and national development.

The minister for Education Science and Technology, Prof Adolf Mkenda, recently announced that since the re-entry policy's announcement, 7,195 students have returned to school, including those who left due to pregnancy.

While this is a positive step, there is a pressing need to address the root causes of school dropout and encourage re-entry in Muleba.

A possible remedy?

The University of Dodoma’s lecturer, Dr Mussa Tabu, believes that vocational training presents an ideal solution.

"As a country, we must be aware that by integrating practical skills training into the curriculum, schools can empower students to engage in income-generating activities without abandoning their studies. I support the upcoming education policy because it fully addresses this element," says Dr Tabu. He further emphasises the need for support networks or systems for teenage mothers, to ensure they can continue their education while receiving assistance in childrearing.

"The environment for the safety of their children must be considered as well. With the certainty of their children being safe, especially in areas close to schools, many will return to the formal system without any problems because most of them wish to continue studying," he says. Dr Tabu calls for the encouragement of diverse income-generating opportunities to reduce reliance on a few sectors, thus allowing students to pursue their education. He adds, "Raise awareness within communities about the importance of education, dispelling the myths that lead to early dropout."

Muleba's struggle with school dropout due to economic activities paints a sobering picture of the challenges faced by teenage mothers and students.

While the government's policy marks a positive step towards addressing the issue, an education consultant, Dr Thomas Jabir, says there remains a long road ahead in terms of changing mindsets, expanding opportunities, and empowering young minds to break free from the cycle of poverty and invest in their education.

“The allure of immediate financial independence through income-generating activities in Muleba is undeniable, but it comes at a significant cost to the education and future prospects of the district's young population. The re-entry policy must address all these diverse challenges,” he says.